Non-state armed groups in the sky

- Contextual knowledge of armed non-state groups, including how they access and use drones, is key to developing an effective regulatory framework that specifically targets armed non-state groups.

- Although state support plays a role in the proliferation of drones to non-state actors, key non-state armed groups engage in tactical and technical innovation to build in-house capacity.

- The dual use of drone technology makes it difficult to impose export restrictions, and circuitous routes make it hard to track drones, hampering efforts to legislatively restrict the spread of drones.

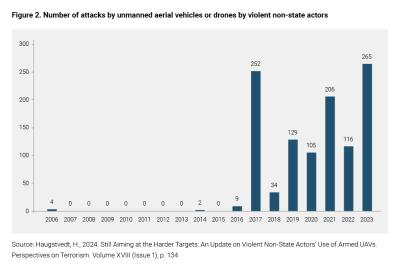

The proliferation of inexpensive and user-friendly, civilian-grade drones represents an escalating security concern for states. Currently, over 65 non-state actors are known to possess drones, and the unregulated nature of drone usage suggests that this number will continue to rise unchecked.

Drones are revolutionising conflict dynamics as they provide non-state armed groups with a means to conduct surveillance, gather intelligence and execute precision strikes. This technological advancement grants these groups strategic influence previously unattainable without substantial resources.

While the UN is concerned about the proliferation of drones, more work should be done to grow the knowledge base in order to identify, develop and use appropriate regulatory frameworks to counter their spread. The accessibility of drone technology has the potential to exacerbate conflict, posing a growing threat to global security. Recent events underscore the security threat posed globally by drone acquisition by non-state groups. These include non-state armed group responses to Israeli attacks on Gaza, with more than 170 attacks on US bases in Syria and Iraq from October 2023 to February 2024, injuring nearly 200 and killing three US troops. Meanwhile the Houthis in Yemen have maintained a months-long campaign targeting international shipping in the Red Sea with both drones and missiles.

The proliferation of drones

Drones can cause damage and disruption hugely disproportionate to their cost.

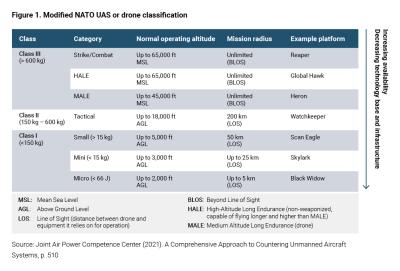

The use of drones by non-state armed groups poses an increasing threat to regional and international security. Drones include air, ground, surface and underwater platforms, but uncrewed aerial systems (UAS) are particularly widespread because of their versatility. These systems – defined as vehicles that can be piloted either remotely or semi-autonomously – vary in size, weight, endurance, wing type and other characteristics. There are no globally agreed upon definitions or typologies of drones, although NATO does offer one approach based on weight.

While state sponsorship allows some non-state actors to attain more advanced models, evidence suggests that most non-state armed groups use commercial or homemade models. These models are cheap and designed to be user-friendly, which allows for experimentation and customisation with various munitions. This is spurred on by sharing of expertise and capabilities among different armed groups, including through online and social media channels. Several African states have also confiscated manuals with instructions on drone use that suggest information transfer between African non-state armed groups as well as also from the Middle East to Africa. Additionally, due to miniaturisation, vertical take-off and landing, and autonomous flight features, drones require limited infrastructure and can be used by smaller, tactical groups, which increases flexibility.

Tactics and trends in drone use

Non-state armed groups adjust drone use to the context; choosing between fixed-wing UAVs with explosives that either detonate on or close to targets, and quadcopter-type UAVs with four or more rotors positioned horizontally, which have the advantage of being able to hover over designated targets. While each group uses drones in a manner that is unique to its own set of logistical, political, and strategic parameters, some overall characteristics can be identified.

First, non-state armed groups prefer, but do not limit themselves, to hard targets. Since 2020, energy infrastructure, international shipping, international airports, and capital cities have all been targeted by drones, but direct targeting of civilians is unusual.

Second, non-state armed groups use drones to conduct intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) missions. Such missions serve to map out routes and guide attackers. The UN mission in Mali (MINUSMA) has frequently reported drone sightings shortly prior to being attacked by armed groups.

Third, the vast majority of drone strikes by non-state armed groups take place in the Middle East and see the operation of one or just a few centrally controlled drones. However, drone swarm technologies, where up to thousands of drones fly autonomously, coordinating with limited human interference through AI and local sensors, are emerging as a future threat.

Fourth, non-state armed groups can use drones for targeted killings, understood as the deliberate, premeditated killing of selected individuals. The apparent assassination attempt on Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro during a public speech in 2018 by weaponised miniature drones illustrates how even miniature drones can constitute a threat to public order and safety.

Finally, the status and prestige associated with possessing drones can itself become a primary objective, rather than effectively striking high-level targets. Drones are also used to produce propaganda by filming attacks, training or other activities, which can deflate enemy morale and project power. This is particularly prominent among affiliates of Islamic State and Al-Qaida.

Countermeasures to drones

The head of US Central Command has warned that consumer drones are hard to defend against while easy for adversaries to use. Low velocity and altitude can make them difficult to detect on radar and the existing options to (cost)-effectively defeat them are limited. While civilian drones can be neutralised using conventional firepower, this response typically costs far more than its targets do. The Houthis in Yemen boast about the cost to the US of their Operation Prosperity Guardian in the Red Sea, as the price in itself is testament to the impact of the Houthi operation. Other options include the use of nets to capture drones, of high-power lasers, of microwaves to damage or jam drones’ sensors, and the targeting of drone operators or targeted killings of major drone commanders. But non-state armed groups continuously innovate and learn from each other to find ways to neutralise existing counter-drone technology, for example by diminishing the drone’s acoustic signature. Moreover, when drones operate autonomously, jamming the link between the drone and the operator or its satellite link is less effective.

Absence of enforceable international regulation

The UN Secretary General has highlighted the perils of the proliferation of drones among both state and non-state actors in the absence of sufficient governance frameworks, and the UN Counter-Terrorism Committee has identified the spread of drones as a key terrorist threat, leading to a number of declarations (such as the 2022 Delhi Declaration), memorandums and more practical guidelines to address this threat. But so far these efforts have had little impact for several reasons.

First, while military drones tend to have higher endurance and be larger than civilian drones, the distinction is becoming increasingly blurred with continued technological advances. Unmanned combat aerial vehicles are included among conventional arms, but while drones have traditionally been piloted remotely or semi-autonomously, drone navigation and object-identification functions are increasingly enabled by artificial intelligence. The regulation of automated drones is challenged by the absence of specific multilateral regulations for lethal autonomous weapons systems.

Second, the international deterrence system is based on states as the unit of analysis, and non-state armed groups are typically less vulnerable or amenable to state-based tools such as sanctions or travel bans used by the international community to uphold international regulatory frameworks. Additionally, there is no multilateral arms control mechanism dedicated to comprehensively addressing threats posed by drones, and while there are some national mechanisms for arms export controls in place, these vary in formalisation and stringency, with some nations explicitly or implicitly eroding existing export control regimes for political or economic purposes.

Practically, the imposition of export restrictions on drones has been challenged by the dual use of drone technology and the lack of a clear distinction between civilian and military drones. This is further exacerbated by difficulties in restricting software diffusion (e.g. program codes, algorithms, data), which might soon affect and define weapon systems performance more greatly than hardware. Civilian purchasing pathways are diverse and accessible through general platforms such as Amazon, making it almost impossible to control acquisition, while circuitous routes make it hard to track drone components. Also, so far the emphasis has been on voluntary cooperation with the private sector. The UN Institute for Disarmament Research has argued that due to the blurring of lines between civilian and military drone technology, differentiation should focus on capability. Moreover, arms control mechanisms could focus on key weapons-related components, although on-the-ground innovation would challenge the effectiveness of these measures.

DIIS Experts