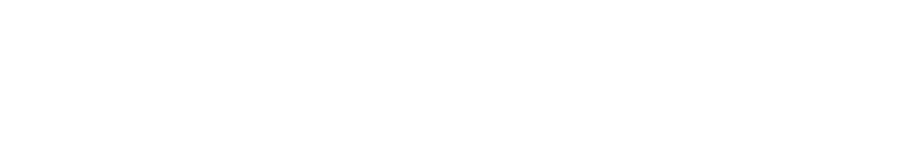

Six months of anxiety and boredom: How poor Brazilians cope with life under quarantine

“We get stressed at home, hot-headed, nervous, wanting this thing to end soon, for us to go back and live our lives the way it was. I never expected to live what we’re living now.”

These are the words of Rafaela*, spoken during a recent interview about the impact of Covid-19 and life under quarantine. Rafaela lives in Salvador, a city of over three million people on Brazil’s northeastern coast. She is 38 and lives with her 7-year-old daughter at her grandmother’s house in a public housing project on the outskirts of the city. Since mid-March, she has been stuck at home.

Six months after the first case of Covid-19 was confirmed in São Paulo in late February 2020, the president, Jair Bolsonaro, declared his crisis response ‘unparalleled in the world’, despite Brazil’s dubious top ranking as the country in the world with the second highest Covid-19 death toll.

Bolsonaro continues to oscillate between downplaying the severity of the virus and denying it altogether, and he has repeatedly claimed that social distancing and quarantine measures are bad for the economy. But neither lives nor the economy have been saved; on September 1st, Brazil officially entered a recession. On September 15th, Brazil reached 132,000 deaths caused by Covid-19, making the disease the cause of death with most victims ever registered in a single year (including both natural and unnatural causes, such as homicide).

How has the government responded to the crisis and how is it affecting the lives of the poor? At this point, many people fear poverty more than the pandemic.

Before the Covid outbreak, Rafaela made a living from street vending and poorly paid cleaning jobs. Her total income was below the poverty line. She would sell things like umbrellas on rainy days and homemade plastic flower arrangements on special occasions like Mother's Day. Two weeks after the first cases were reported in Salvador in early March, the mayor, ACM Neto, ordered people to stay at home. Schools closed and so did many commercial activities. Public transport was either reduced or shut down.

Since the quarantine was imposed, Rafaela has only been called once for a cleaning job. With most people at home, and many people on reduced salaries, the women who used to call her are taking on the domestic chores themselves. And with few people in the streets and consumption in the city significantly reduced, few people are buying so it is not worth the effort or the risk to go out and try to sell her goods. Rafaela’s grandmother has diabetes, and she therefore has to be careful not to bring the virus home.

The grandmother’s house is a small two-story house of forty-two square meters, where Rafaela shares the upstairs bedroom with her daughter. In the living room there is a couch with a purple cover and bright green cushions and a bookcase with plastic flowers, family photos, figurines and a TV. Her grandmother spends most of the day at a small wooden table covered by a colourful tablecloth, watching TV and doing crossword puzzles. She learned to read and write when she was almost 80 and practices every day.

Unbearable quarantine

The quarantine measures in Salvador go against president Bolsonaro’s virus-related orders. Since the onset of the crisis, an ongoing battle between the president and mayors and governors has ensued over quarantine and other prevention measures. Municipal elections are scheduled for November 2020, which heightens the pressure on municipal authorities to contain the devastating impact of the coronavirus.

We have to distract ourselves, from everything that is happening, to try to stay well”

Although Rafaela knows that the quarantine is meant to stop the spreading of the virus, she finds it unbearable. For someone who is used to be out every day and “correr atrás”, as she says, meaning to be hard-working and constantly trying to earn money, it is very difficult to be forced to stay at home. It is also hard on her daughter who has nothing in particular to do. She spends most days watching TV. Rafaela has trouble sleeping at night because of all her worries, and sometimes she tries to sleep the day away.

“When I'm getting sad, I put music on and start singing. I say to myself: ‘I can't be sad, I'm healthy, I'm walking, I can do everything I like despite this quarantine’. Then I turn on the sound and sing, to feel better”.

Rafaela continues: “We have to distract ourselves, from everything that is happening, to try to stay well”.

The virus arrived in Salvador via elite Brazilians returning from vacations in Italy. As in other Brazilian cities, they passed it on to their friends at glamorous wedding parties and dinner parties and then to their domestic workers. The domestic workers brought the virus to the poor communities across the city. At the beginning of September, Salvador was the city in Brazil with the fourth highest infection numbers and the fifth highest death toll.

Covid-19 and fake news

Rafaela has long stopped watching the news. Like many other people interviewed for this article, she finds it too distressing, especially the news on the novel coronavirus. Also, discussions over fake news, have left people like Rafaela a bit confused about what to believe. Fake news and disinformation are ongoing issues that have intensified during the pandemic. Often times, incorrect or misleading information about the virus has come from the president himself, who has had his social media posts deleted by Facebook and Twitter for spreading disinformation.

Fake news and disinformation are ongoing issues that have intensified during the pandemic"

Bolsonaro has repeatedly accused the mainstream media of causing hysteria and even called the pandemic fake news. In June, mistrusting the media reports of hospitals overcrowded with coronavirus patients, Bolsonaro encouraged his followers on Facebook to break into hospitals to video-record and report on ‘the real situation’.

In early June, the country’s Covid death toll and accumulated number of infections were removed from the website of the Ministry of Health, in an attempt to control the news on the virus, and, according to Bolsonaro, reduce fear in the population. The supreme court ordered the government to resume publishing the numbers.

Emergency aid to the poor

Between May and August, Rafaela received coronavirus emergency aid, auxílio emergencial, from the federal government. The push for emergency aid came from a coalition of over 160 Brazilian civil society organisations and movements.

In April the Emergency Basic Income was approved by congress and the senate, with some revisions, and, later, by the president. The monthly rate of the emergency aid ultimately approved (600 BRL (USD 110) and 1200 BRL (227 USD) for single mothers) was much higher than the Bolsonaro administration own proposal of a flat rate of 200 BRL (37 USD).

Around sixty-five million people received the benefit, including the self-employed, unemployed, and informal workers like Rafaela. Due to bureaucratic failures, not everyone who was entitled to it received the money, while some people who were not entitled cheated and managed to get it. Still, it prevented millions of Brazilians from falling below the extreme poverty line.

The benefit has been extended four months, from September to December, but at a reduced rate of 300 BRL (56 USD), and 600 BRL for single mothers (110 USD) which, for many people, will not even cover their rent. Luckily for Rafaela, the state-built public housing where she lives is rent-free so she does not risk being evicted like many other poor families in Brazil.

One of Rafaela’s neighbours, Lucia, is grateful for the emergency aid, which is much higher than her monthly income before the crisis. This mainly consisted of the conditional cash-transfer program, Bolsa Famíla (family stipend) and occasional informal street vending. Bolsa Famíla is the Brazilian government’s flagship social program on poverty alleviation. Poor families receive cash every month on the condition that their children follow the child vaccination programme and attend school.

As a single mother, Lucia received the high rate of the emergency aid, which Rafaela was also entitled to. But despite Rafaela’s efforts to correct the mistake by calling and going to several social assistance centres, she continues to receive the standard rate.

In addition to the emergency aid, Lucia’s has received so-called food baskets, cesta básica, with food staples like rice, beans, milk, and sugar. She receives one of these food baskets for each of her children. Providing staples to poor families was an initiative from municipal authorities to tackle the potential epidemic of malnourishment among children when schools closed; schools provide a free meal for poor children that is often their main meal of the day. Lucia donates one of her baskets to an elderly neighbour who lives alone. Lucia’s children are enrolled in public schools whereas Rafaela had prioritised paying for her daughter to go to a local private school. For this reason, she has not received food assistance.

Bolsonaro’s popularity boost

Bolsonaro was originally against the emergency aid, but now it turns out that it has increased his popularity among the poor and even among the poor in Brazil’s two most impoverished regions, the North and Northeast. The Northeast, in particular, has been a stronghold for the Worker’s Party in presidential elections, and the state of Bahia - where Salvador is located - is no exception. Bolsonaro only won in four out of the state’s 417 municipalities. Recognising that such social policies could very well be his re-election ticket, Bolsonaro has changed his attitude towards Bolsa Familia, which was launched by the Workers Party in 2003.

Forty-seven percent of Brazilians believe Bolsonaro has “no blame” for the country’s coronavirus deaths"

This is a radical shift for Bolsonaro, who has long been a fierce opponent of Bolsa Famíla. He cut the program once he became president and has made numerous derogatory remarks about its beneficiaries. Bolsonaro ran for office on an anti-Worker’s Party platform. He frequently demonizes its supporters and blames the party’s fourteen years in government for nearly all that he considers wrong in the country. During the latest election, he received many so-called ‘protest votes’ because voters wanted change and did NOT want the candidate from the Worker’s Party to win the run-off in the second round.

Bolsonaro had announced a new program, Renda Brasil (Brazil Income), to replace Bolsa Famíla, but disagreements between Bolsonaro and his minister of economy over the financing of Renda Brasil has postponed its launch to 2022.

Bolsonaro has also embraced another Worker’s Party flagship social program, the public housing program Minha Casa Minha Vida, which he relaunched under a different name in August. Despite Bolsonaro’s anti-Worker’s Party rhetoric, his new re-election strategy for the 2022 presidential elections is starting to resemble Worker’s Party priorities.

The emergency aid and the decision to prolong it, although at a reduced rate, increased Bolsonaro’s approval rating to 37 percent, which is the highest since he took office. For some voters, the monetary aid speaks louder than the widespread critique of Bolsonaro’s poor handling of the health and economic crisis or his indifference - and at times outright condescending attitude - towards the victims of Covid-19 and the crisis itself.

Bolsonaro’s refusal to take responsibility for the course of the crisis in the country also seems to have paid off. A poll late August showed that forty-seven percent of Brazilians believe he has “no blame” for the country’s coronavirus deaths, despite his fierce engagement against social isolation measures and discrediting of the use of face masks.

Bolsonaro has also opposed science-based recommendations while promoting the anti-malaria drug, hydroxychloroquine, as a cure despite the lack of evidence. Disagreements over Bolsonaro’s anti-science responses to the pandemic led the president to fire two health ministers, which has left the country with an ineffective interim health minister from the military for four months. On September 16, he was made full minister and backs Bolsonaro’s promotion of the anti-malaria drug. Forty-nine percent consider Bolsonaro’s efforts during the Covid crisis as bad or terrible.

At the onset of the Covid crisis in Brazil, there were heated discussions of impeachment of the president. But because of his relatively stable popular support throughout the crisis and his recent increase in popularity, Bolsonaro has avoided the more than fifty impeachment inquiries that the speaker of Brazil’s Congress has received and, so far, dismissed.

Money shortage and rising food prices

Among the people who have not received the emergency aid and who are now struggling to pay their bills is Elisangela, a woman in her mid-fifties. She is a kindergarten teacher in a private school, where she also works as a secretary. Since the quarantine was imposed, many of the parents have unenrolled their children out of school to avoid paying tuition fees. Elisangela has received only ten percent of her salary.

“With 10 percent what can I buy?” she asks rhetorically. “Nothing,” she responds. “Absolutely nothing!”

Basic food items like beans have increased by more than 30 percent"

Her husband works as a bus driver, and because of the restrictions on public transport, he, too, has received a reduced salary, along with millions of workers in Brazil. Because Elisangela and her husband remained employed, they are not entitled to apply for the emergency aid.

For many poor Brazilians like Rafaela and, currently, Elisangela, it has become hard to pay their monthly expenses. This is further complicated by a sharp rise in food prices in Brazil, a trend across the Latin American continent during the pandemic. Basic food items like beans have increased by more than 30 percent. Families also have new expenses, such as face masks, hand disinfectant, and disinfectant cleaning products. At first, they were hard to get a hold of and difficult to afford, but the supply has become steadier and prices have become more reasonable.

Elisangela lives in one of the poor neighbourhoods in Salvador for which strict lock down measures were imposed in late May because of elevated infection rates. Check points controlled by military police prevented people from entering the neighbourhood unless they are residents, and residents’ movements outside the neighbourhood were restricted to essential activities. While the lockdown is lifted, quarantine measures continue. Many commercial activities remain closed, as well as the city’s beaches, while essential services, such as supermarkets and pharmacies, are open at reduced hours from 10 am to 4 pm.

Battling multiple epidemics

Elisangela is a devoted evangelical Christian. This is reflected in the way she describes life during the pandemic.

“The present is a time of mourning that must be lived with calm. We have to live this time of illness, this time of sadness. The Bible says there is a time for all things.”

Bolsonaro’s rhetoric has been one of prioritising the economy over human lives"

Many people we have interviewed express distress over the way that everything suddenly stopped. No one was prepared for a crisis like this, and they just want it to be over. Being forced to stay at home, worrying about their health and livelihoods, and the uncertainty of when it will end, has brought people a lot of emotional stress.

Many of Rafaela’s neighbours have suffered adverse effects of the emotional stress, which negatively impacts chronic illnesses like high blood pressure and diabetes. Both Rafaela and her grandmother struggle with these diseases. Elderly people, in particular, fear going to the hospital for treatment and then contracting coronavirus. One of Rafaela’s neighbours recently died from a heart attack in her home.

Only a few of Rafaela’s neighbours have been infected with the coronavirus. Lucia is one of them. She was very sick and had all the symptoms, such a high fever and the loss of smell. At the local health post, she was not tested but told to go to the emergency room if her condition worsened. Other mosquito-borne illnesses are even more common. Lucia was sick with the zika virus last year, which, she told us, was “much worse.”

The poor are battling several epidemics at the same time. And so far, there is no cure for any of them"

Many neighbours in the housing complex have been ill with chikungunya virus, dengue and zika. According to Bahia’s health authorities, infection levels have been on the rise in 2020. Chikungunya alone had increased by 434 percent by June.

One of the mothers we interviewed had been so worried about coronavirus that she did not let her children go anywhere; then her daughter got the zika virus while at home and was very sick for weeks. In addition to the struggle to make ends meet, the poor are battling several epidemics at the same time. And so far, there is no cure for any of them.

When will things get better?

Many people are hoping for vaccines to combat the pandemic so life can return to normal. Brazil has partnered with vaccine developers from Britain and China, which are doing large clinical trials in the country. Brazil has invested in more than 100 million vaccines (for a population of 211 million). The government is also negotiating with other vaccine developers, but it is still unknown when one will be ready.

Bolsonaro’s rhetoric has been one of prioritising the economy over human lives. That is why he did not support quarantine measures and, instead, argued that vaccines would resolve the epidemic. However, beginning of September, the president declared that no one will be obliged to take the vaccine, which has sparked outrage. Whether this will be the official government position once the vaccines are ready, remains to be seen.

I don’t think the tendency is that things will get better. They will get worse”

Whether or not Bolsonaro maintains his current popularity also remains to be seen. It depends on many factors, but mainly on the country’s economic recovery. Brazil had just barely started to recover from its recent economic crisis, which began in 2014, when the Covid crisis started to impact the country.

Elisangela told us her biggest concern was: “the country’s economy. How are we going to help ourselves in this economy? There is no prospect of life returning to the way it was.” She continued: “I don’t think the tendency is that things will get better. They will get worse”.

Rafaela and Lucia expressed deep worries over their household economies once the emergency aid comes to an end and job opportunities are even fewer than before. In May, Salvador regained its position as the metropolitan city in Brazil with the highest unemployment rate.

In July, across the country forty-one million Brazilians were out of work according to Brazil’s national statistics bureau. In addition, many who work in the informal economy are unable to work due to stay-at-home measures, without officially being registered as unemployed. In Salvador informal workers make up more than forty percent of the workforce.

The mothers we have interviewed have all pointed out that their children have suffered from being forced to stay at home for six months. Now mid-September, there is still no date set for when schools will reopen. Some children have been given homework.

Lucia has been going to the schools of her two youngest children to collect homework assignments once a week, while her teenage son has not had any assignments. Similar to what many parents have done at the school where Elisangela works, Rafaela unenrolled her daughter to save money. She plans to enroll her again when the new school year starts in February.

Overall, the people we have talked to worry about the coronavirus, and they know it is infectious and potentially deadly. But at this point, they fear poverty more. As Rafaela said: "We are living a life now without peace.”

*The names of the interviewees are pseudonyms to protect their identities. The interviews were conducted in August 2020 over the phone as part of a qualitative study on life under quarantine among the urban poor in Brazil, which is undertaken by Marie Kolling and Thaise Sá Santos. The study is part of Marie Kolling’s ongoing research in Salvador, initiated in 2012.